Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire

The very concept of "franchise films" evokes McCrappy food and a "serve 'em up, shove 'em out, 'next!' attitude" that wouldn't seem to mesh with the desire to dine well. It's the rare sequel that provides anything new, much less substantial or tasty. Amazingly for Hollywood, the first three Harry Potter films hadn't taken that tack -- if anything, the producers may have almost been a bit too respectful of the books. They treated the books as biblical, errorless, fundamentalist documentaries on the wizarding life.

Still, probably because of that respect, the first three films were successful, in both tone and character, capturing the sense of magical whimsy that made the books so compelling to such a wide range of readers. The effects were, almost without exception, devices that served the story, rather than ends in and of themselves.

So, when the 4th film was to be directed by a new director, and to star someone other than Richard Harris as Dumbledore, trepidation flew on greasy wings into the abyss of my muggle heart (hey, if one can't mix weird metaphors in one's own blog, where can one mix 'em?).

Fears unfounded. "Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire" is a qualified success. Of course, one doesn't go into this film with the same expectations as, say, a Merchant/Ivory flick, but that shouldn't diminish the (almost) complete fulfilling of said expectations. This film (like it's biblically-rendered sourcebook) is dark (as the whole series gets darker and darker). Semi- major characters die; Voldemort emerges alive and predatory; Harry and his cabal endure rifts and teenage angst and hormonal assault.

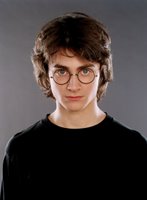

This last point teeters on one of the weaknesses of this film (and scary future of the series): Daniel Radcliffe, the titular star, is 16 years old (when Harry is supposed to be 14). He looks a lot older than that. When Harry becomes pubescent, will it look a little weird to have a 6 foot tall, twice-daily-shaving actor playing him?

This last point teeters on one of the weaknesses of this film (and scary future of the series): Daniel Radcliffe, the titular star, is 16 years old (when Harry is supposed to be 14). He looks a lot older than that. When Harry becomes pubescent, will it look a little weird to have a 6 foot tall, twice-daily-shaving actor playing him?"Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire" also feels like a movie that is missing some key scenes. The book explored the fear and pain and heartbreaking emotions of first love. The movie, for the most part, simply glosses over that -- and in the one section of the movie in which it plays a major part (Harry and Ron and Hermione at the ball), dropped scenes reduce the section to filler material.

Voldemort could have been scarier, Dumbledore could have been more imperial, Sirius could have had more than one small scene played in a box of coals. This might be particularly notable, given Sirius's importance to the next book/movie). Still, these are quibbles with a movie I enjoyed very much.

By the way, don't you just love the pornsound of the phrase "titular star"?